I know what you’re thinking. Why does a blog centered on quitting your job post about minimum wage and taxing the rich? While they’re mostly though experiments, to be financially free and entrepreneurial you must know your economic and political environment. Having a business or investments is highly impacted by what goes on in the political Thunderdome.

As with the thought experiment on Fight for $15, I want to walk through whether or not “taxing the rich” is a viable solution economically. “Tax the rich” has become a battlecry of several 2020 Democrat Presidential Candidates, as well as political policy in a bevy of states such as Oregon, where Senator Ron Wynden proposes taxes on ‘unrealized gains’ of assets of wealth people, or the governor of Illinois wanting to revamp the state tax code to make the wealthy pay more in state tax. Targeting the rich has become en vogue.

But does it work? It has been tried before and abandoned, so why would it work this time? Is it moral or fair? Does “tax the rich” merely promote classism? Is it biting the hand that feeds? Or is there social stability to be gained from it? It’s time to dig into it.

What is Rich?

When a politician says they want to “tax the rich,” what defines rich? In many cases it’s left intentionally vague — the “rich” being a boogeyman of sorts, the anachronistic caricature of a monocle and top hat wearing Rich Uncle Moneybags from the game of Monopoly. It’s Mr. Scrooge or the bourgeois of The Purge films. So who are The Rich?

According to Charles Schwab’s 2019 Modern Wealth survey, “Americans believe it takes an average $2.3 million in personal net worth to be considered “wealthy.” Another survey by seniorliving.org landed on the same number: $2.3 million as the amount to be considered wealthy.

Elizabeth Warren’s “Ultra-Millionaire tax” targets the rich as any household with a net worth of $50 million or more. Bernie Sanders’ proposal starts the taxing on net wealth over $32 million, a level which fellow 2020 Democratic candidate Tom Steyer agrees with. However, it appears “rich” is a relative term: according to Forbes, the net worth of these three candidates is $12 million, $2.5 million, and $1.6 billion, respectively. So, although Warren and Sanders are millionaires, they don’t consider themselves rich. And as for Steyer, I get suspicious whenever someone who is rich promotes taxing the rich.

So we have a starting point (somewhere between $32 and $50 million) for what qualifies for a “wealth tax.” Federal and state income tax brackets vary wildly (some states have a flat tax while others have no income tax), so we’ll stick with the proposed Federal “wealth tax” as a guideline for what is considered rich.

Do Higher Taxes Equal Higher Revenue?

“Nothing is more calculated to make a demagogue popular than a constantly reiterated demand for heavy taxes on the rich. Capital levies and high income taxes on the larger incomes are extraordinarily popular with the masses, who do not have to pay them.”

Lugwig von Mises

The purpose of raising taxes on the wealthy — or instituting “wealth tax” — is to raise the amount of funds taken in by the state or federal government. But does it always go as planned?

The fallacy of taxing the rich to me is the assumption that those being heavily taxed will just sit there and take it. Take the case of actor Gerard Depardieu after France instituted a 75% “supertax” on their wealthy citizens. The actor famously renounced his French citizenship and moved to Russia, later threatening to sell all his French assets left behind. Depardieu wasn’t alone: an estimated 2.5 million French citizens left their home country to live elsewhere and the loss of labor, combined with “discouraged investment”, crushed French tax revenues by a 14 billion euro shortfall of the 30 billion euro estimated intake. The French wealth tax, called the “solidarity tax on wealth,” was eventually repealed in 2017.

Other European countries tried a wealth tax and eventually repealed it: Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Sweden. (Sweden in particular become notorious for its wealth tax after Swedish children’s book author Astrid Lindgren paid 102% in income tax in 1976. Because she was self-employed, she was subject to both regular income tax and employer’s fees, resulting in being taxed over 100% for that year. The Pippi Longstocking author later wrote satirical children’s book about the incident called Pomperipossa in Monismania)

Due to capital flight, it was estimated that the French wealth tax actually reduced France’s GDP (gross domestic product) by 0.2% or 3.5 billion euros.

But back to the wealthy just “taking it” when higher taxes are instituted. It seems asinine to think that a wealthy person wouldn’t act according when faced with the prospect of the government taking more. University of Toronto economist David Seim found that “an increase in tax is likely to stimulate evasion” in his paper Behavioral Responses to an Annual Wealth Tax: Evidence From Sweden. He found that when a wealth tax went into effect, those targeted would shift taxable assets to tax-exempt assets, thereby legally lowering their taxable net worth below the threshold. In addition, wealth taxes — including Warren and Sanders’ proposed American taxes — is a tax on net worth. This means debt is deductible. So borrowing money would thereby reduce overall taxable net worth — and if you’re borrowing to invest in tax-exempt assets, you’re reducing your taxable net worth even further.

The problem is trying to hit a moving target. Those the wealth tax focuses on are affluent, mobile, and have the ability to fight back (more on that in a moment). It’s human nature to respond to someone (or something) that’s coming to take what you have. The rich business owner defends the assets he’s acquired as a caveman defends the prey he killed. The London Times wrote in 1894 in regards to Britains first progressive tax rates that “even the half starved crow will not wait to be continuously shot at.”

The current income tax structure also allows a bevy of deductions for real estate depreciation or cost of improvements; ‘tax loss harvesting’ allows for losses to be written off against gains, creating a net zero effect. A ‘rabbi trust‘ allows companies to give additional compensation that doesn’t count towards taxable compensation. Or take Senator John Kerry, who simply docked his $7 million yacht in Rhode Island instead of Massachusetts, saving him nearly $500,000 in taxes.

Ronald Reagan’s tax planning is just one simple example of how the rich can easily avoid the upper tax brackets. Someone noticed what a fine golf swing Reagan had, and the answer was that when he reached the top tax bracket, he stopped working and played golf for the rest of the year. Many wealthy doctors (and others) do the same thing, closing down their medical practice around August and then taking a vacation from earning money for the rest of the year. A government cannot force a wealthy taxpayer to work if the taxpayer finds the tax rates personally intolerable, especially if they are targeted for attack.

Charles Adams

Or you just leave altogether like Depardieu or Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin, who left the U.S. for Singapore and saved hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes.

Magnus Henrekson and Gunnar Du Rietz studied the history of the Swedish wealth tax. They found that “people could with impunity evade the tax by taking appropriate measures,” including taking on excessive debt to buy exempted assets. The Swedish wealth tax also prompted large outflows of capital and the expatriation of well-known business people, such as the founder of Ikea, Ingvar Kamprad. Henrekson and Du Rietz conclude, “The magnitude of these outflows was a major motivation for the repeal of the wealth tax in 2007.”

“Why Europe Axed its Wealth Taxes” by Chris Edwards

The point is, politicians expect to collect x amount in tax revenue assuming that those taxed do not respond or act in any way. Charles Adams wrote an article in 2004 called “The Rich Wont be Soaked” (source also for the quote above) showing that it’s always been this way:

History is full of amazing examples, like the first income tax in the United States, in 1916, when the top bracket was 7 percent; a few years later the top bracket was raised to 77 percent, or 11 times higher. Yet the 77 percent rate did not produce 11 times as much revenue; in fact it shocked the Treasury by producing almost the same revenue as the 7 percent rate did. At the 7 percent top bracket, about 1,300 returns were filed; with the 77 percent top bracket, only about 250 returns were filed. Where did all the top bracket taxpayers go? The rich simply rearranged their affairs to avoid the 77 percent tax rate.

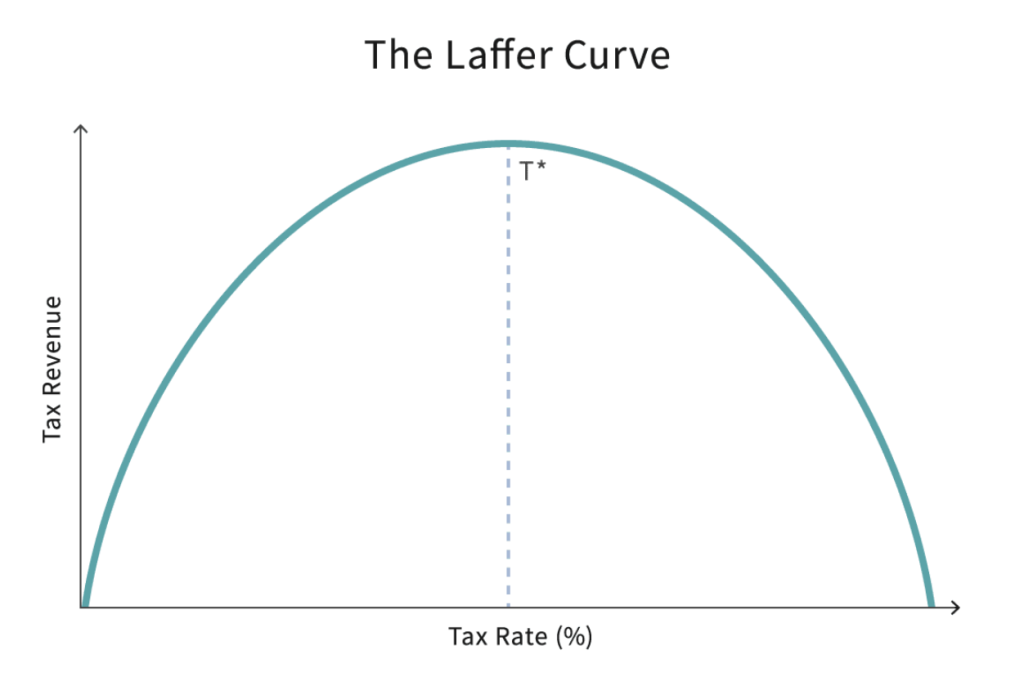

Which brings us to the Laffer curve. Arthur Laffer believed people would adjust their behavior “in the face of incentives created by higher income tax rates.” The result was the Laffer curve, a graph showing more dwindling returns the higher the tax percentage. It essentially is a visual representation of the points mentioned above.

As the tax rate becomes more burdensome, the behavior to avoid increases. This could be through changing investments to tax friendlier ones or not investing at all. The end result either way is less tax revenue.

Enforcement

There is also the matter of enforcing the new laws and costs associated with them.

Recently, the IRS admitted to congress that the poor are far more likely to get audited than a rich person, because it’s easier and cheaper; the IRS told Congress it could be solved by an increase to the IRS budget. Elizabeth Warren’s plan specifically mentions “a significant increase in IRS spending” to help ensure no eligible wealthy person evades audit. After all, Warren, Sanders, and other wealth tax plans are a tax on all worldwide assets. The IRS is going to need to assess assets and wealth held overseas as well.

An even larger problem lies not in logistics but valuation. “All household assets” will be including in a wealth evaluation for the wealth tax. Cash, stocks, and property are somewhat easy to assess. But what about art? Family heirlooms? Will the IRS hire jewelers to assess the value of the family pearls or diamond rings? Maybe the Pawn Stars guys can evaluate what’s in the basement and attics of rich Americans. There seems to be no guidelines on estimating the worth of fringe assets. How about a privately-held businesses owned by the taxed wealthy? With no quarterly earnings report, an auditor will have to assess the full value of the private company — down to desks, equipment, and credit card bills. The valuation of a company can change even daily given the flow of business. And how do you value a multi-national company when taking into account currency exchange rates and overseas assets?

And this would have to be done every year.

Elizabeth Warren address this in her plan:

- Valuing assets for the purposes of the Ultra-Millionaire Tax will provide an opportunity to tighten and expand upon existing valuation rules for the estate tax:The IRS already has rules to assess the value of many assets for estate tax purposes. The Ultra-Millionaire Tax is a chance for the IRS to tighten these existing rules to close loopholes and to develop new valuation rules as needed. For example, the IRS would be authorized to use cutting-edge retrospective and prospective formulaic valuation methods for certain harder-to-value assets like closely held business and non-owner-occupied real estate.

Bernie Sanders takes it a step further, requiring a “wealth registry,” something not defined on his website but presumably a government record of assets held by an individual.

Both of these creates a dark precedent: the government will come into homes to assess “assets”, taking record of what you own, and assign value to it. While there are guidelines to valuation, they’re ultimately left up to the IRS. Does this mean the IRS would also begin to operate internationally? The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act already requires U.S. nationals with foreign assets or holdings to claim such holdings and for banks to report the individual’s funds to the U.S. government. But what about art or cars at foreign homes?

Enforcement at home and abroad comes with a cost. More tax officials and inspectors, more paperwork, more travel and expenses just to enforce the wealth tax. These costs go against any revenue raised by the taxes themselves. But do they effectively offset? There’s an issue of scale here: to fully realize maximum tax receipts, expenses associated with enforcement must also be maximized. Costs of enforcement could also rise over time while tax receipts could go down; in theory, the entire intake of tax revenues could be spent on enforcement.

Unintended Consequences

Because this is a thought experiment, we can assume the above headache of multi-national asset holding valuation gets done on Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos (a favorite target for Warren and Sanders). His numerous holdings and assets are assessed and valued. It comes in close to Forbes’ October 2019 valuation of $103 billion. Under Elizabeth Warren’s plan, Bezos would be subject to 6% wealth tax (2% tax since it’s over $50 million and additional 4% billionaire surtax since the number is over $1 billion). 2% tax on $1 billion is $20,000,000. The 4% surtax on $102,999,999,999 is $4.2 billion (rounded up). Combined, that’s $4.22 billion owed in wealth tax (which does not include Federal, state, and local income tax or capital gains taxes). And this amount is conservative compared to CNBC’s estimate of $9 billion Bezos would pay under Sanders’ 8% wealth tax.

Here’s where it gets interesting. The likelihood Bezos has that amount in pure cash is highly unlikely. His personal wealth comes from his ownership in Amazon, specifically his shareholdings. To cover the $4.22 billion owed, Bezos would have to sell 2.5 million shares of Amazon stock (based on its current valuation of $1,745 per share). But even then that wouldn’t be enough because Bezos would owe capital gains tax on selling the stock. He would have to sell additional shares just to cover capital gains on the 2.5 million shares AND the shares he was selling to cover the tax (as of this writing, long term capital gains tax on Bezos’ tax bracket is 20%)

The result is that Bezos is forced to reduce ownership in his own company to pay wealth tax; the selling of 2.5 million shares by the CEO would also likely cause panic in stock (including knowing he’d have to sell more the following year), driving it down in price as investors get spooked. Since Amazon is a commonly held stock in 401ks, IRAs, and pension portfolios, all are hit by the selling. Bezos is not alone in the tax. Other billionaires will be forced to sell company stock to pay wealth tax bills, thus retirement funds will bear the brunt of reduced stock value from each of these companies.

The other choice Bezos and other owners have is to liquid company assets to pay the tax bill. This is money taken out of the company — money that could be reinvested for growth or was originally earmarked for new projects and initiatives. The loss for the company translates into higher costs passed on to customers or cutbacks in jobs or pay. This would also likely result in a stock price decrease.

In either case, by the time the next tax season rolled around, the overall valuation would be less — either by selling off $4.22 billion (plus capital gains tax) in stock or by reduced stock price in the company due to devaluation. Maybe the following year, Bezos is worth less than $100 billion. Yes, he’d still be subject to the wealth tax at 6% (or Sanders’ 8%) but the tax receipts would be less than the previous year. So the amount of tax receipts would drop, offsetting less of the enforcement costs and costs to social programs instituted by the president candidates.

Think of it this way: Social program (SP) plus additional wealth tax enforcement costs (EC) equal the projected tax receipts from the eligible billionaires in the United States.

SP + EC = Billionaire Tax Revenues

The balanced equation gives the presidential candidates what they want – their taxes pay for their new spending. But if Bezos and other billionaires suffer a reduction in net asset value, the tax revenues will go down over time. Now the social program and enforcement costs are not being covered by tax revenues and there’s a shortfall. Now you have to either reduce the SP spending (which would be unpopular), or reduce EC spending, which makes it more difficult to enforce the tax which would likely result in even less tax revenues. The only other choice is more government debt to make up the shortfall.

What happens if Bezos pulls a Depardieu and leaves? Now he isn’t contributing any tax revenue (except for his one-time exit tax) and the shortfall is that much larger. He may decide to do just that: at some point, Bezos will have sold enough Amazon stock to threaten his voting ownership and control of his company. The value of Amazon stock could plunge if he lost control due to lack of ownership — further reducing the value of American pension plans and retirement portfolios.

This also raises the moral question of is it right to take away ownership of someone’s company just because it was successful to a high enough degree? Wouldn’t this de-incentivize future entrepreneurs and business people? After all, why build a company beyond a certain point if a wealth tax will cost you ownership? It’s Ronald Reagan hitting the green all over again.

So there you have it. While the wealth tax attracts populist attention, the reality behind it is murky at best. It has been tried in the past and ultimately withdrawn due to failure to meet results. If anything, the shift in behaviors will create disruptions in the economy — and worse the possible flight of capital to foreign shores. With less to wealth to tax, the shortfall needs to be made up somewhere, either in increased government debt or taxes on lower classes who can’t leave.

Based on this thought experiment, do you think a wealth tax is still viable? Comment below!